Samhita Arni is the author of “Sita’s Ramayana”, a graphic novel developed in collaboration with Patua Artist Moyna Chitrakar and published by Tara Books. The book has spent two weeks on the New York Times Bestseller List for Graphic Novels. When she was eight, Samhita started writing and illustrating her first book. “The Mahabharata – A Child’s View”, (Tara Books, 1996) that went on to be published in seven language editions, selling 50,000 copies worldwide, winning the Elsa Morante Literary Award, and receiving commendations from the German Academy for Youth Literature and Media and The Spanish Ministry of Culture.

Congratulations on the success of ‘Sita’s Ramayana’. The text for Sita’s Ramayana, I understand, was woven around Moyna Chitrakar’s art work. How was the experience of doing this? Did the paintings offer you the chance to convey exactly what you had wanted to in your retelling of Ramayana from Sita’s perspective?

I know it’s surprising – but I didn’t meet Moyna until the launch. She did the illustrations and then I wrote the text around her images. The visual narrative

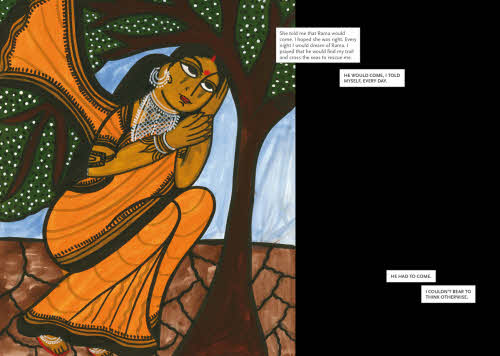

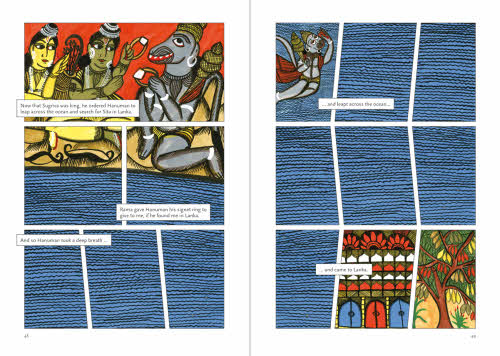

Sita’s Ramayana is a collaborative effort – I’d like to emphasize that – it’s the product of many conversations and discussions between my editor, publisher, layout designer etc.– Moyna’s images – is primary. So in the text, I’ve tried to remain true to the spirit of the images, and not impose my perspective if it doesn’t complement Moyna’s point of view as expressed in the artwork. The artwork came first, and then the text – so the textual narrative is woven around Moyna’s images. At a few places I had to ask her to draw a couple of more images – for example, when retelling the story orally it’s not difficult to switch viewpoints. But in this book, we felt it would be best to stay with Sita’s point of view.

Incidentally regarding my perspective, I have a novel out through Zubaan later this year on Sita, it’s a speculative-fiction-feminist thriller. A few chapters were excerpted in Caravan.

I believe as a child too, you were fascinated about mythology. So has it been the case that you had wanted to understand (and perhaps retell) Ramayana from Sita’s point of view from a young age? Or is it an interest that bloomed fairly recently? What kind of research went into writing the text? Did you particularly look into versions of the Ramayana told from a woman’s viewpoint? What were they and what are some of the most important aspects that such narratives explore?

As a child, growing up, I never really engaged with Sita’s character. She was a collection of virtues, the ideal woman, wife, submissive and demure. I wasn’t really interested in her until I came back to India, after being abroad for a decade.

When I returned, I found my life circumscribed in many ways – but also, there was at times, a thrilling sense of empowerment. It’s hard to explain. But it struck me that you couldn’t make any generalisations about India. Things here are complex and layered – I always thought that Sita was a demure, submissive figure – and I couldn’t relate to her as a girl growing up, ambitious, determined to make the most of the opportunities that were offered to me, see as much and experience as much as I could. But when I came back, I discovered that there were women who sang songs about Sita, wrote about Sita in the kitchen, in her trial, on her wedding day –and in each of those things, the frustrations that Sita experienced, the circumscription, the lakshman rekha – these were symbolic, women spoke about their own imprisonment and issues through this. And there was a sense of empowerment. Sita became a more complex figure – the Ramayana became a more complex, layered and engaging epic for me.

The epics and myths, particularly the Ramayana, have a constant history of reinterpretation and retelling, but that seems to have dwindled now – and I think it’s important to retell the epics to keep them current, alive, for these stories to continue to resonate. The epics are fantastic for so many reasons. As a writer, I’ve learnt so much about literary craft (metaphors, metonyms, character arcs, etc.) just from reading the Valmiki Ramayana and the Kamba Ramyana. And these stories are part of our consciousness – they’re transposed on our landscapes, we watch them on TV, in films, they’re there in our puja rooms, in the paintings and carvings in temples – it’s so influential.

The epics and myths, particularly the Ramayana, have a constant history of reinterpretation and retelling, but that seems to have dwindled now – and I think it’s important to retell the epics to keep them current, alive, for these stories to continue to resonate. The epics are fantastic for so many reasons. As a writer, I’ve learnt so much about literary craft (metaphors, metonyms, character arcs, etc.) just from reading the Valmiki Ramayana and the Kamba Ramyana. And these stories are part of our consciousness – they’re transposed on our landscapes, we watch them on TV, in films, they’re there in our puja rooms, in the paintings and carvings in temples – it’s so influential.

The Ramayana is not just an epic – it’s a tradition that is self-reflective, one that spans many countries, many different forms, written, oral and visual, in many different languages. It’s a tradition in conversation with itself. It’s amazing and incredible when you think about it. And that’s made me realise that the Ramayana is SUCH a powerful story, and speaks so strongly to so many.

What is it that intrigues you about Sita?

There’s more to her – there has to be, she endures so much in the epic. She has to be strong, she’s put through so many trials – I’ve tried to suggest that strength in the narrative.

Here, we have given her a voice – with her point of view, that hopefully makes a reader empathize, and engage more deeply with her circumstances – her captivity, her hopes, her fears, the tragedies that consistently happen to her (exile, capture, war, distrust, the agony pariksha, also she’s abandoned when pregnant.) Hopefully that makes her a stronger character.

At the moment of the agni pariksha – I’ve tried to imagine what Sita thought. She would have been furious, upset, confused (and that’s there in Valmiki’s Ramayana) – I’ve emphasized that. She’s suffered so much, so many have died, so many women have been widowed – and now Ram doubts her? I make her say – “War, in some ways is merciful to men. It makes them heroes if they are victors. If they are the vanquished – they do not live to see their homes taken, their wives widowed. But if you are a woman – you must live through defeat.” She goes on to say, “I thought the end of the war had meant freedom for me.” It doesn’t – instead of love, justice and freedom, she meets with accusation, distrust and anger.

Looking at the end, Kamban’s Ramayana, for example, ends with Sita and Ram returning to Ayodhya. Valmiki continues the story – Sita is abandoned in the forest, raises two children, and then encounters Ram. When that happens, instead of going back to Ayodhya, she beseeches her mother to take her. In my opinion – when Sita rejects Ram’s offer to return to Ayodhya, if she proves her virtue again – it’s a powerful moment, and powerful statement. She doesn’t need to prove her virtue over and over again, she’s already proved it once and be doubted – so what’s the point? She rejects being a queen, of a people who rejected her, to a husband who abandoned her in a forest even though she was pregnant with his children. Through the ages, many have been uncomfortable with that ending – is it a tragedy? Why, when Ram comes back to her, does she choose not to return? How do you understand that point in the story?

Over the years, this is the understanding I’ve come to – I don’t think that moment – moving though it is – need to be seen as a tragedy, it affirms Sita. I’ve tried to communicate that in the book.

What were the challenges in telling the story from Sita’s point of view? How did you tackle them?

It was challenging, particularly when you realise that during the battle in Lanka – which occupies such a prominent place in the narrative, Sita was imprisoned in Ashoka Vana and didn’t see what was happening. The difficulty I faced was how to recount the war, and yet preserve Sita’s perspective? Trijatha, who is Vibhishana’s daughter, occupies a prominent place in Kamban’s Ramayana, she’s Sita’s friend and confidante, despite being a rakshasi. So in Sita’s Ramayana, her role is a little like Sanjaya in the Mahabharata, she describes the war to Sita. I thought that it would be good to develop her more in this version – because, like Tara (Vali and Sugriva’s wife) and Sita – she spells out, she herself lives with and witnesses the consequences of conflict. Obviously, a lot of this Ramayana is also influenced by the Patua oral tradition; the episode, with Renuka Devi-Yellamma, for example, isn’t something that’s found in the ‘classical’ textual traditions. Of course, I also referred extensively to Valmiki’s version.

Taking it a little further, do you feel a retelling of Mahabharata from Draupadi’s point of view presents a broader platform for exploring and expressing a feminist perspective?

It could.

It’s heartening to see that the role and perception of women in our country have been changing for the better over the years. Yet, it goes without saying that we still have a long way to go. In such a context, it is important for a woman to make the beginning from herself: to first feel good about her own self. Do you feel that women can draw inspiration from Indian mythology in this regard? Any particular women from our mythology that you feel are truly inspiring?

Yes, definitely. I suppose any woman can, but it depends on how she relates to the story. For reasons I’ve outlined, I found Sita interesting and inspiring. I think there must be women who find Gandhari in the Mahabharata courageous, who empathize with the tough decisions and choices that Kunti faces, and find an echo of their own experiences of violence and humiliation in Draupadi’s story.

Your third book, also your first work of fiction, is I believe, inspired by Sita and the story of Ayodhya. Can you tell us more about it and what makes you go back to the Sita theme?

I wrote that book first, before Sita’s Ramayana. I had been researching the Ramayana for this other work, a speculative fiction novel. Over three years back, it so happened that I ran into the publisher, Gita Wolf, at the Jaipur Literature festival. We started chatting and I told her about my Ramayana research, and we starting talking about the various Ramayana traditions and versions. It turned out that Gita was working with a Patua folk artist, Moyna, who had a very interesting take on the Ramayana: a narrative that prioritized Sita. Both Gita and I were very excited: and it seemed like a perfect fit, and I jumped at the chance to be involved.

Here’s more about my novel:

Sita (tentative title) is a ‘speculative-fiction-feminist-thriller’ which explores the end of the Ramayana and the consequences of the war in Lanka. In a world that resembles ours, Ram rules over ‘Ayodhya Shining’. But even in this prosperous, perfect kingdom, darkness still lurks. A journalist realises that there are always two sides to history, when she meets Kaikeyi, Ram’s stepmother and former Queen of Ayodhya. Kaikeyi voices the one question that Ayodhyans are afraid to ask – Where is Sita, Ram’s absent wife, whose abduction triggered the Lankan War? And so the journalist begins the quest for Ayodhya’s missing Queen, to ask questions that reveal the ‘other’ side of Ayodhya Shining, and meets both the victors and the defeated from the Lankan War. Soon, her investigation attracts the notice of the Washerman, the head of Ayodhya’s powerful intelligence agency. She is forced to flee to Lanka and Mithila to elude the Washerman and find the one person who has the power to answer her questions, to tell it like it really was – Sita.

Looking ahead, will mythology and feminism be frequent themes in your writing? What features in your future writing plans?

Not sure! But my next work will definitely have nothing to do with mythology, although it’s too early to say what it will be about.

All Pictures copyright of Tara Books. Reproduced with permission.