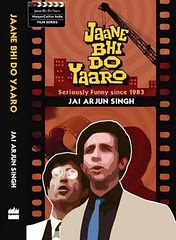

Jai Arjun Singh is a freelance writer and journalist based in Delhi. He writes a fortnightly film column for Yahoo! India and has also written for Business Standard, The Hindu, Tehelka, The Sunday Guardian, Outlook and The Hindustan Times, among other publications. His book about the film ‘Jaane bhi do Yaaro’ was published by Harper Collins India in 2010. He has also edited an anthology of film writing, ‘The Popcorn Essayists: What Movies do to Writers’, for Tranquebar.

Two books on movies, a fortnightly film column for Yahoo! and a blog that deals sizeably with cinema, among others. What is it that fascinates you about cinema and writing about it?

I’ve been a movie buff since childhood, but around the age of 13 I became seriously interested in a variety of films – not just the Hindi films I had grown up with but old American and foreign-language films too. Simultaneously, I started reading a lot of film-related literature, which opened my eyes to new ways of watching movies. I became fascinated by how many different ways there were of visually telling a story – or in some cases, not so much telling a proper story but creating a mood.

I like thinking about the films I watch, and writing my thoughts down. Long before I became a professional writer, I would scribble little notes about practically any film I saw. Once I started working as a journalist and feature writer, it became possible to do this for a living.

a. Cinema is like a mirror that reflects the society for it to see. b. Cinema is a flight to fantasy. It represents all that the average man/woman dreams of. Which of these statements come closest to your viewpoint on the nature and purpose of cinema?

I’ll sound like a fence-sitter here, but really, I’m not a fan of rigid definitions. There can be great films that are primarily mirrors to society, and great films that are primarily “flights to fantasy”, and there can be great films that are some combination of both things. In any case, such divisions can be very misleading. (In the context of literature: great fantasy writing, even if it’s set in a completely imaginary world, can be a mirror to our own society. Though it might require a little more effort on a reader’s part to grasp this.)

If I were ordered to make a statement about “the nature and purpose of cinema” with a gun pointed at my head, I’d probably say something like, “A really good film is one where form and content come together in the best possible way – regardless of whether the subject matter is escapist or grounded in hard realities.”

You write a lot about Hindi movies on your blog. How do you feel Hindi cinema has evolved over the years? (particularly from the 70s to today?)

This would require a full-fledged essay, but briefly: the line between “commercial/mainstream cinema” and “parallel/art cinema” is no longer as clear as before; the multiplex culture has made it possible for even big mainstream stars to do relatively small, experimental films. The best directors of today – people like Anurag Kashyap, Dibakar Banerjee and Vishal Bhardwaj – have had a lot of exposure to international cinema and their approach to movie-making is comparable to that of the 1970s American directors (Scorsese, Spielberg, DePalma, etc) who were film students first and directors second.

Technology has improved, and in my opinion the best films made today are smoother, more visually pleasing than most of the films made in the past. When I say “visually pleasing” I’m not necessarily talking about surface gloss or computer-generated effects or music video-like “stylishness” – what I mean is that in the really good films today, one scene flows naturally into the next and you get a sense of the film as a unified organism. Whereas in the past it was common to see abrupt cuts that were purely functional and convenience-driven; there were jarring shifts in tone and films had a generally episodic quality.

Do you think Bollywood is really an overhyped phenomenon today or do you think it deserves all the attention it has been getting?

Isn’t EVERYTHING overhyped today? No, seriously – with media congestion, furious competition among newspapers and 24-hour channels, added to the fact that we’ve always been a movie-mad country anyway, it’s inevitable that Bollywood is in our face all the time. Movie stars routinely occupy centre-stage even in fields that are way outside their areas of expertise – at book launches, hosting TV shows, even writing Advice Guru columns in newspapers supplements. It’s quite comical at times.

Are you a fan of documentaries? If yes, what is it about them that captures your interest? Could you tell us about some documentaries that you really loved?

This is a big gap in my film-watching, unfortunately. I’ve seen very few documentaries, and the ones that I’m really familiar with – and think highly of – tend not to be “pure documentaries”. I’m talking about films like Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North and Orson Welles’ F For Fake, films that continually blur the line between fictional and non-fictional representations, and in some cases force us to think about the nature of the difference between documentaries and feature films.

You have mentioned in your blog that you used to carry a small notepad around noting down movies and marking them with stars. Has your perception of movies changed over the years? How? It would also be interesting to know whether your reviewing method has changed too!

Well, the first thing to be said is that I’m very snobbish now about the star-rating system! That small-notepad thing you’re talking about is probably from when I was 8-9 years old, when I would rate a film anywhere between 1 star and 16 stars, depending on what took my fancy. (The exclusive, rarefied 16-star rating was of course reserved for a single film, Sholay!) But from there the next step was writing small, unstructured notes about every film I saw. And when I started reading serious literature about films, I understood that allotting “stars” or “marks” was by far the least interesting thing you could do as a reviewer. It was far more important to engage carefully with a film, think about it and articulate your thoughts as well as you could.

Talking about your books, I understand that your first book, ‘Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro’ is part of a Harper Collins series on movies. What prompted you to choose this film over many other choices that you may have had?

movies. What prompted you to choose this film over many other choices that you may have had?

I’ve answered this question so often it’s coming out of my ears. See this blog post for details (http://jaiarjun.blogspot.com/2010/12/yeh-kya-ho-gaya-how-book-came-to-be.html), but briefly: the film was one of the cultural milestones of my childhood. There are so many memories of watching it on Doordarshan on a black-and-white TV set, guffawing away at the comedy but also puzzled and disoriented by the very bleak ending. It’s a very intriguing movie to write about because of the way it uses various modes of humour (satire, black comedy, absurdism, slapstick) for social commentary; there’s hardly anything else like it in Hindi cinema.

Also, so many important people from the world of theatre and parallel cinema were involved in the making of JBDY – I thought it would be interesting to do a book that was part-reportage, part-analysis.

How was the experience of researching for the book? I believe you met members of the cast and crew and spoke to them. Tell us about it!

I spent a lot of time with writer-director Kundan Shah in particular, and I also spoke to Ranjit Kapoor (the dialogue writer, described by Kundan as the film’s architect), Naseeruddin Shah, Ravi Baswani, Satish Shah, Om Puri, Binod Pradhan, Sudhir Mishra and others. Getting Kundan to open up took a bit of time, and I was nervous because being based in Delhi, funding my own travel and working on other things simultaneously, I didn’t have the luxury of making frequent trips to Mumbai. But once he was convinced about the project, it was smooth going.

One of the highlights was a long chat I had with Pawan Malhotra, who had gone to Mumbai in the early 80s to become an actor but found himself working as a production assistant on this film, doing all sorts of odd jobs such as going to a municipal building to collect a dead rat for a two-second shot in the film! Pawan was a joy to talk to, very warm and forthcoming. Ravi Baswani (whom I met a year before his death) was very candid too.

One thing I keenly felt the absence of: not being able to speak to Renu Saluja, the wonderful editor who passed away a few years ago; she was a key player in the Jaane bhi do Yaaro story.

And before I ask you about your second book, I must say lovely title – the popcorn essayists. Tell us how the book came about. What made you decide on coming up with a collection like this?

I think there’s a lot of potential in India for intelligent yet accessible long-form film writing. The Tranquebar editor Deepthi Talwar and I were talking about this and we thought it would be interesting to commission film-related pieces by established writers – novelists, short-story writers – who don’t write professionally about cinema. That way we’d be assured of quality writing as well as a fresh perspective. And we’d let them choose their subjects.

I think there’s a lot of potential in India for intelligent yet accessible long-form film writing. The Tranquebar editor Deepthi Talwar and I were talking about this and we thought it would be interesting to commission film-related pieces by established writers – novelists, short-story writers – who don’t write professionally about cinema. That way we’d be assured of quality writing as well as a fresh perspective. And we’d let them choose their subjects.

For the title, full credit goes to the effortlessly creative Manjula Padmanabhan, who is one of the contributors to the book.

How was the experience of putting the anthology together? What was that one common feature that you felt emerged from the pieces?

It’s been very satisfying. I consider myself fortunate because when you’re putting an anthology of original writing together on a deadline, you usually have to make little compromises here and there. But in this case, nearly everything came together very smoothly – there were only a couple of writers who backed out at the last minute – and every writer in the book is someone whose work I have a basic regard for.

Common feature? Good writing about cinema, with a personal touch – that’s it. The tones and styles vary – for example, Namita Gokhale’s piece about her days publishing a gossipy magazine in the 1970s is chatty and free-flowing, while Anjum Hasan’s piece about the films of the Kaurismaki brothers is more formally structured, in the style of the classical long-form journal essay. But they are both high-quality pieces of writing about how cinema intersected the author’s life in some way.

Finally, what’s the next book coming out of Jai’s stable? Give us a teaser!

No plans for another book as of now. I’m not the sort of guy who’s likely to get addicted to book-writing; perhaps because I’ve worked on the literary beat for a few years now, I’m quite blasé about the publishing process and I don’t get an adrenaline rush from seeing my name on a book. Right now I’m happy with the longish reviews/columns I get to write for some publications, and with the space that I always have on my blog. Definitely need more practice in the field of long-form writing though (by which I mean essays that are 5000 words or more in length).

If I do another book at some point though, I think it will be a film-related book again.

Rapid Fire with Jai

Two movies you would watch N times over

Cruel question, impossible to answer. (In fact, I recently wrote a column about the fact that it’s much more practical to think in terms of watching favourite sequences repeatedly rather than whole movies – especially when there’s always so much to keep up with, so much viewing and reading to do and so little time.) But let me give an honorary mention to the first hour of Hitchcock’s Psycho. It’s always a hypnotic experience for me.

Five Unforgettable characters (across languages/genres)

Can I skip this, please? Okay, I’ll do it – but bear in mind that the list would be completely different if you asked me to do it again after a minute. And completely different again after another minute. And so on. It would be easier to do this if you asked for a list of 1000 unforgettable characters. But just off the top of my head:

– The tragically disfigured girl, wandering her father’s mansion alone with a white mask on her face, in Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face

– Mr Scratch (a.k.a. The Devil) as played by Walter Huston in The Devil and Daniel Webster

– The revenge-seeking ichaadhaari naag in Jaani Dushman: Ek Anokhi Kahaani, which was Raj Kumar Kohli’s remake of his own 1970s film Nagin. Kohli’s blank-expressioned son Armaan Kohli played the Reena Roy role in the remake, which is one of the most eye-poppingly entertaining movies I’ve ever seen

– Joan of Arc, as hauntingly played by the magnificent Maria Falconetti in The Passion of Joan of Arc

– And I’ll end by being horribly clichéd and saying: Gabbar Singh in Sholay

One advantage that Indian cinema has over Hollywood

Difficult to say. Speaking potentially: the fact that, being an ancient and varied culture, we have access to a large treasure trove of stories, which can provide good material – and inspiration – for writers. But I don’t know if that resource is being used enough.

Your thoughts on South Indian movies

Have hardly watched any, sadly, though I love S Srinivasa Rao’s Pushpak.

A book on cinema that you have enjoyed

There are dozens, but here are some I have very special affection for: Robin Wood’s Hitchcock’s Films Revisited, V F Perkins’ Film as Film, Danny Peary’s Cult Movies series, Joy Gould Boyum’s Double Exposure: Fiction Into Film, Pauline Kael’s For Keeps, Peter Conrad’s The Hitchcock Murders, Garson Kanin’s Tracy and Hepburn, Kirk Douglas’s The Ragman’s Son, David Thomson’s Have You Seen…? and Luis Bunuel’s My Last Breath.

Multiplexes or ordinary theatres?

The last time I went to an “ordinary theatre” – though there was nothing particularly ordinary about it, apart from the fact that it had a single screen – was at the elegantly revamped Delite cinema in central Delhi. But generally speaking, it’s been multiplexes for the last few years.

Your idea of a perfect movie review

Firstly, a really good review (and I’m ideally talking about a long review here, not a 300-word snippet) must stand up as a good piece of writing on its own terms – something that is both a pleasure to read and a mind-opener. The reviewer should be an intelligent, perceptive person who has some background knowledge of what he’s writing about – so, for example, if he’s reviewing a film, it would be great if he’s familiar with the director’s/crew’s previous work so he can make observations about recurring themes, visual motifs, contrast the film with an earlier film, and so on.

The review should be personal in the sense that it provides the reader with a sense of how a particular individual has responded to a particular film. It should open a window to a perspective that might be completely different from your own but be so well-expressed that you have to nod your head and say, “I disagree with this guy, but I understand what he’s saying and where he’s coming from.”